Everything Else is Mystery

After He Said Cancer | A Memoir

His name was Tripp Hudgins, and his background defied a simple explanation. After Divinity School, he completed a fellowship in the spiritual care of the dying and patients with trauma. Along the way, he worked as a Baptist pastor and a teacher at many levels. He spent time studying how music has shaped religious practice at Berkeley. He was also a talented writer, blogger, and musician.

He had ‘fallen in love’ with chaplaincy. He was deeply passionate about helping people in a vulnerable place. Spiritual care of the dying was a way for him to integrate his work as a pastor and expertise in helping people grappling with trauma and grief. Sometimes, he even brought his guitar to the hospital to play music and sing to a patient.

On so many levels, we were different. My working life was in rainy Seattle, thinking about molecular biology and infectious disease. His working life was in sunny Virginia, providing spiritual care for the dying and helping people navigate trauma and grief. I could rarely remember the artist of a song, in any genre or any decade. Tripp was a musicologist, who incorporated music into his everyday life, and even sometimes in his work as a hospice chaplain.

He answered my call on an online writer’s platform to discuss experiences with grief and cancer.

Would the insight of a hospice chaplain be of interest to your listeners, he asked me in an email.

Yes, I said, and was surprised by the joy I felt in having the chance to speak with him. I have so many questions for you, I wrote back.

While I was waiting for him to join my video call, I wondered what I asked him. The page for taking notes in front of me was blank. Instinctively, I knew that it wouldn’t be a problem to arrive at an opening question to ask him. It wasn’t even a question, really.

More than anything, I wanted him to tell me what was wrong with me.

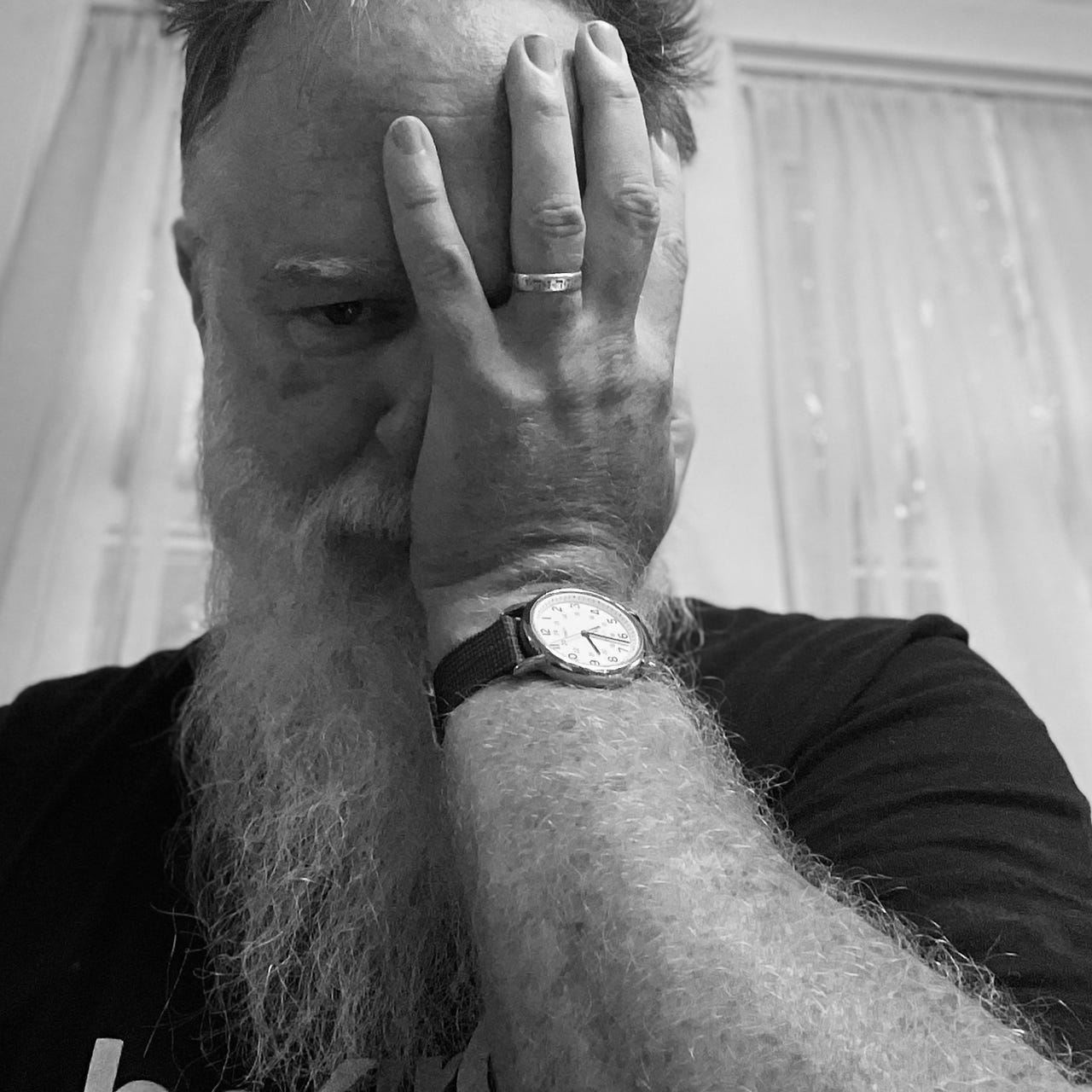

His video popped up on my screen. He had a long, white beard and steely blue eyes, but they were very kind. Something about his appearance or calm demeanor put me at ease.

Whatever it was, it must help him to gain the trust of patients and families, I thought. I wondered how many dying patients and grieving families he had worked with. And what he had learned about helping people in this world find peace in the most trying of days.

“My husband’s cancer diagnosis doesn’t fit with the picture that I have in my head of us growing old together,” I said, voice cracking. “We have young girls who need him, desperately. They need their father, and I just can’t lose him.”

“It’s not a question of liking it,” he said, pausing for a moment. “At some point, you need to accept the reality of what you are facing. Even if it infuriates you or throws you into despair.”

He paused again before choosing his words carefully.

“I don’t say this to make it sound easy, because it’s not,” he said. “It is the hardest thing to do. But at some point, you will find acceptance.”

Acceptance? Hadn’t I accepted his diagnosis? Of course, I had. If anything, I realized more than anyone that his life would be cut short by this disease. My eyes were wide open on this point. But if we peeled back the layers of the onion, he was getting close to the crux of the issue. Achieving a deep and emotional acceptance of his cancer and what might happen was not in my vocabulary.

To me, acceptance meant that I had to surrender to what was coming.

Never retreat, never surrender, a slogan of the US Marine Corps, was much closer to a philosophy that I could embrace. My father had been a Marine in World War II and Korea. He had survived more than 30 days on Iwo Jima crawling from bunker to bunker, surviving on sheer grit.

“My grief counselor said that I would suffer less if I could accept this. But I can’t. Nor do I want to. Why should I accept this?” I said with a particular emphasis on the ‘why’. Perhaps this was what a man of God could explain to me – WHY I should embrace what would surely be my ruin.

He looked at me squarely and took a breath. This wasn’t the first time that he had encountered someone with a perspective like mine, I could feel it.

“The hard reality you are facing is that this is coming, whether you accept it or not,” he said. “I agree with your grief counselor that you will suffer less if you can accept this. But if it is more like you to fight this until the bitter end, you do that. You fight it.”

“Acceptance can bring peace, but peace may not be the end goal,” he continued. “Sometimes people go out fighting because that is who they are. I had one patient who was a fighter, and he was salty to the bitter end. If he told me that in death he would have been embraced in the arms of his loving God, it would have been completely out of character. No, he was angry – all the way to the end.”

“I happen to be Christian,” he said. “In my brand of Christianity, finding peace is important. I pray for peace a lot with people, often because it is not present. Part of ‘acceptance’ is that you may not find peace. I love it when peace comes, and people have a peaceful end. But as a Chaplain, I must face the reality that peace will not always come.”

Was he saying that I may not find peace with my husband’s cancer diagnosis? Possibly. But if finding peace might be elusive, maybe I could accept that my struggle was part and parcel of who I am and my way of grieving.

“Each family is different. Each death is different. How people grieve varies,” he pronounced. Again, I wondered how many times he had seen the end of life with all of its variations and nuances. The way that he suspended judgment of the grieving was a relief.

“There’s no singular approach other than to be open to what comes next and to be kind…unflinchingly kind,” he said.

The video began to look blurry, and I could feel the tears running down my face. He had seen through my anger and the walls that I had erected around my pain. And with kind eyes and kind words, I could no longer hold back my tears.

“Kindness allows for grief and joy to exist simultaneously. Grief is a kind of love and love leads to joy. And as much as we may miss our loved ones, we can still experience joy. It’s okay to laugh. It’s okay to cry. It’s okay to do them both at the same time. There are few if any rules here,” he said.

No rules? This helped me. In the moment, I could feel a light bulb turning on inside my soul. He was saying that my way of grieving was OK, and that I shouldn’t be hard on myself.

If it was my personality to be a fighter, and clearly this was true…then it was OK that I was fighting with his cancer and myself in my head. I could accept that my ability to find peace might not come as easily as it would for someone else and might not come for a very long time.

We sat in silence for a moment as I processed what he was saying. This conversation could lead to a breakthrough in my grief and understanding of myself, if I could think deeply about what he said and withhold self-judgment. I would also need to throw out the window my prior ideas about grief and the stages that people go through. Or just embrace that I might be stuck in the ‘angry’ phase for a long time.

“The truth is there are no perfect answers. We just live through our last days…and everything else is mystery.”

*****************************************************************

For more insights into life, end of life, and the meaning of it all, consider subscribing to Tripp’s blog, the “Lo-Fi Gospel Minute”. I am a paid subscriber, because I enjoy reading his Franciscan nuggets and want to support his work.

******************************************************************

If you would like to read other posts that are part of my evolving memoir (After He Said Cancer), here are a few:

How It Began. This story is the origins of my blog, and tells the story of the first moment when we learned of my husband’s breast cancer diagnosis. https://www.afterhesaidcancer.com/p/how-it-began

A Beach Surprise. A nice day at the beach turns into something else entirely, thanks to our mischievous animal. https://www.afterhesaidcancer.com/p/a-beach-surprise

A Queen. The story of a dear friend that lost her husband to breast cancer.

100 Different Fonts. A conversation over breakfast turned into a question as to why cancer couldn’t easily be cured. Read on for my answer.

*********************************************************************************************************

Thank you for being one of my readers. I appreciate you very much! If you’d like to support my work you can do so by:

Hearting this post, so that others are encouraged to read it. (This helps others to see my posts.)

Leaving a comment (I do my best to respond to each of them), which increases engagement and visibility of my posts

Sharing this post by email or on social media

Taking out a free or paid subscription to this Substack

Leaving me a tip by buying me a coffee.

After He Said Cancer is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you so much for including me. I am grateful for your generosity.

Grief is indeed different for everyone. And it can last a long time, at least it has for me. My husband died in 2020 and my son (from breast cancer) in 2021. I still have trouble talking about either of them without tearing up. I didn’t start grieving their loss until after they died, but I took care of each of them and was too busy with that work at the time. Give yourself grace…this is the hardest journey you will travel in life. Sending hugs.