It’ll Just Kill Plants

It won't hurt you. It's just to kill plants. It's called Agent Orange...and it won't bother humans. – Karl Marlantes in Matterhorn

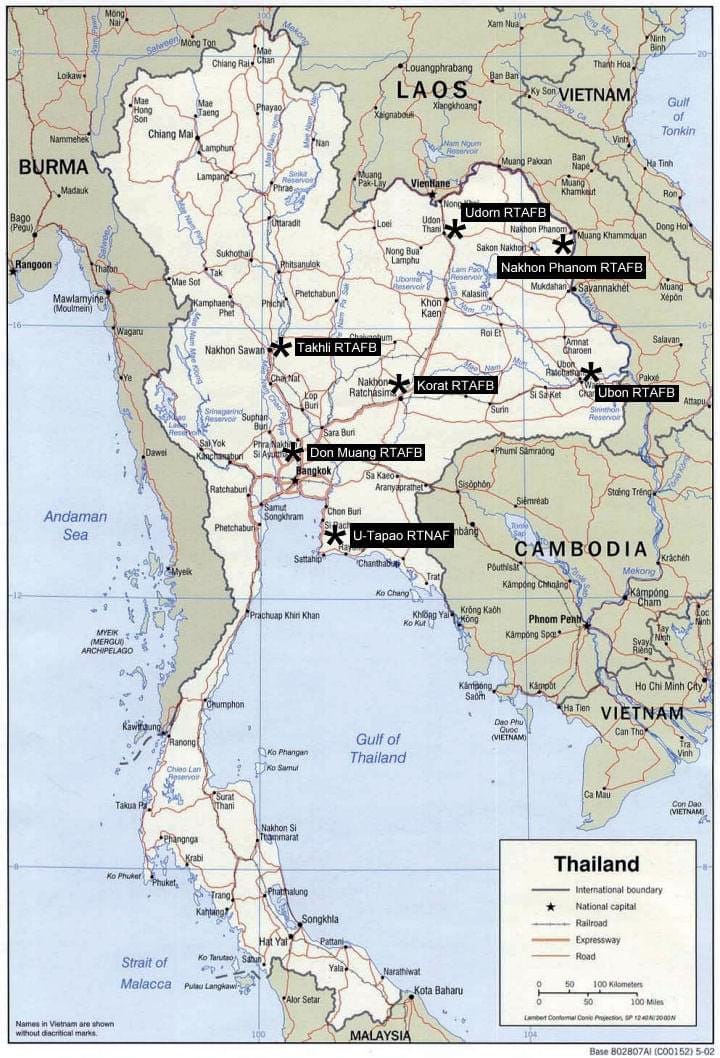

“I was stationed at the U-Tapao Navy airfield in Thailand for B-52’s and other aircraft flying back and forth to Vietnam. They sprayed the perimeter of the base with Agent Orange every day,” he said in between bites.

We were packed into a small, private dining room in a restaurant in Kansas City: me, a male breast cancer survivor and his wife, and the woman who brought us all together. She became one of the most prominent advocates for male breast cancer in the U.S after her husband died of male breast cancer. We ended up in an overstuffed maroon booth, getting to know each other over dinner and exploring our terrible common bond.

“I don’t understand,” I said. “Why did they spray the area around the base?” History wasn’t my strong suit. I had traded that part of my brain and college courses for science and medicine.

“It was a jungle. Agent Orange helped to keep the vegetation from growing so thick that you couldn’t see the enemy. When you look at the photos, you just see dead grass surrounding the base. That’s because it killed everything,” he chuckled with a levity in his voice that offset the topic’s gravity.

We were silent for a few minutes as we focused on the dinner. I did a quick internet search on Agent Orange. About eleven million gallons had been sprayed over the jungles of South Vietnam – and in Thailand, around the U-Tapao military base that was supporting the war with aircraft.

“It had a musty smell that followed you. You could even smell it in your clothes,” he said.

I stopped taking notes and looked up. “Why could you smell it on your clothes?” I asked in disbelief. I couldn’t imagine smelling any kind of chemical on my clothes.

“The water they washed the clothes in was contaminated. It got everywhere,” he said with the same levity in his voice and eyes twinkling.

I liked his dry humor about the military’s failings and recognized it from my upbringing with my father, a veteran of World War II and Korea. A sense of humor went a long way when you were serving your country, recovering from combat, and dealing with decades of military bureaucracy. The military wasn’t perfect, but for many men, it created strong, lifelong bonds that were like a family. Families aren’t perfect either, but you stick together through thick and thin. Making light of the military’s failings was a long-term survival strategy.

“The government passed a new law this year called the PACT Act to finally provide benefits to veterans serving in Thailand with health problems related to Agent Orange. Previously, only Vietnam veterans and sailors on ships within 8 miles of the coast had been included. It took 50 years for them to admit that Agent Orange or chemical herbicides had been used in Thailand,” he said with another chuckle.

I had heard that benefits for a young man with breast cancer, who was born at Camp Lejeune, hadn’t materialized either. Can you put a price on the time in one’s life that is lost from premature cancer and the loss for their family? No. I couldn’t even put a price tag on what our family had gone through so far or what might come in the future.

I looked down at my drink and thoughts drifted to my husband and his premature cancer. We had a conversation about this topic a week ago when I finally voiced the questions rolling around in my head.

“Could you have been exposed to herbicides or pesticides when you were growing up?” I asked. He had lived on a farm with well water for parts of his childhood.

“I don’t know. This would have been forty or fifty years ago,” he said shrugging off my question and returned to washing dishes.

As a physician, I would have never seen the point of trying to figure out why a person developed cancer, if it wasn’t a genetic cause. I would have judged myself as grieving in an unhealthy way on a hopeless mission that could only bring me pain. But in my identity as a wife and a mother, the idea of losing my precious husband to an exceedingly rare cancer was something I couldn’t imagine. I couldn’t see it from a clinical perspective. It wasn’t logical. I couldn’t wrap my brain around it.

“Why can’t I stop thinking about this?” I asked him, aware that I sounded a little crazy.

“It is the scientist and analyst in you that prevents you from letting it go,” my husband replied calmly and without hesitation.

“That’s true,” I replied. “But don’t you agree that it is strange? Why is it that two of the four men that I know with breast cancer were exposed to Agent Orange? Sure, the men that fought in Vietnam are now in their 70’s, the age when male breast cancer is typically diagnosed. But only 5% of men eligible for the draft ever served in the war. It seems like too much of a coincidence.” Both men exposed to Agent Orange had extensive genetic testing that turned up nothing.

“I still wonder whether you had a toxic exposure growing up that we don’t know about,” I said searching his face for validation.

His eyes looking back at me projected no energy or fire to fuel my quest.

“People didn’t know much about toxic waste back then. We didn’t even wear sunscreen,” my husband laughed. He had accepted his cancer and moved on to more important things in life.

The waiter brought in the dessert and my daydream evaporated. I was back in Kansas City with three adults that had lived with the fallout from male breast cancer for much longer than my family.

“Sometimes it feels like we are beating our head again a wall,” said the woman on my right, the advocate for male breast cancer. She was talking about advocacy for men with breast cancer, but the analogy worked for me, as well.

I was beating my head against a wall with myself…to understand something that couldn’t be understood.

I like this title/rubric!

Excellent writing, spellbinding!